Three out of every four people have, to varying degrees, some sort of dysfunctional experiential/emotional relationship with God. In September of 2006, Baylor University published the findings from a religious survey they took in partnership with Gallup in a report titled “American Piety in the 21st Century.”1 The survey had over seventeen hundred respondents who answered nearly four hundred questions that dealt with a variety of topics on religion in America. Of note for this article is the finding on the character and behavior of God. Participants were asked twenty-nine questions that revealed the respondent’s belief about God along a scale of God’s engagement level (y-axis) and God’s anger level (x-axis), which fit into four different categories: 1) Benevolent God, 2) Authoritarian God, 3) Distant God, and 4) Critical God. Interestingly, 71.8% of respondents’ belief about God fit into a non-benevolent category. Thirty-one percent believe God is highly engaged and highly angry (authoritative), 24.4% believe God’s engagement is low, as is his anger (distant), and 16% believe God is not very engaged but is highly angry (critical). Twenty-three percent of Americans believe God is highly engaged and not angry (benevolent). Five percent denied God’s existence. According to this survey, 77% of people, or three out of every four people, believe God is angry, distant, or critical, or they reject God altogether.

In the summer of 2014 I began a personal journey of grappling with the dysfunction of my own experiential/emotional relationship with God. This journey has taken me into the worlds of psychoanalysis, neurobiology, attachment theory, biblical studies, the ancient Near East, spiritual formation, and the everyday practicalities of discipleship to Jesus, all in an attempt to understand why so many (including myself) struggle to experience the love of God in our day-to-day lives. Sometimes it is easy to read statistics like the ones above as just another survey that has some interesting insight, but doesn’t really move the needle much. These are symbols and digits printed on a page. However, my personal research has borne out a very different reality. As part of my doctoral work, I developed an assessment designed to expose the unique experiential/emotional relationship each person has with God, then took a focus group from a large evangelical church in Dallas through this assessment. The statistics held: three out of four had an insecure relationship with God. But these weren’t symbols and digits on a page. They were people baring their souls, looking for solutions and answers to questions they knew were real but did not quite know how to ask. We were on a journey of discovery together to find out what the Spirit was doing in and among us to heal serious deficiencies in our own formation. After all, if the Baylor study is touching on what Richard Lovelace calls a “sanctification gap,”2 and if my own research is even remotely close to what is actually real, then we must admit that while many people (leaders, teachers, and lay alike) may affirm an orthodox nominal creed, the vast majority do not substantively experience the reality to which that creed attests. We may adhere to an orthopraxis that manifests in various external activities like study, prayer, and evangelism, but if we actually experience God primarily as angry, distant, or critical, we are in danger of warranting Isaiah’s (and later Jesus’) assessment: “These people come near to me with their mouth and honor me with their lips, but their hearts are far from me” (Is 29:13, Matt 15:8, Mk 7:6).

We are at an inflection point in the life of the Church with crises at every turn: leader failure, moral ambiguity, division in almost every sphere, societal pressure, the frenetic pace of life, global instability, technological advances outpacing our ability to regulate, economic challenges, just to name a few. What the world needs more than anything right now is substance and depth . . . people who don’t merely talk about the transformational love of God, but embody it deeply, and bear witness to a broken world that Jesus is the King. The situation is serious, but I have ample reason for hope. I believe God is inviting us further up and further in, and is beginning to reveal a way forward for his people not only to affirm the love of God, but experience it in profound ways. I know this has been my story and the stories of many others I’ve had the privilege of journeying with, a story that began in a disoriented pool of tears as my subconscious, implicit belief about God was shoved in my face.

Into the World of Psychoanalysis

The road to my current understanding of discipleship and spiritual formation began with an exercise in June of 2014. Betsy Barber, associate director of the Institute for Spiritual Formation at Biola University, was guest lecturing at the second summer intensive for my doctoral cohort. She gently guided us through an exercise that seemed innocuous, but blindsided me and left my soul filleted out on the table in a tangled mess of emotion. I must have scared her because immediately following the exercise I beelined it for her to figure out what she had just done to me, and how. She graciously recommended a resource that I immediately purchased and began to delve into. Of all the people on the face of the planet, I was the last one I would have expected to dive into the world of psychoanalysis. But so I did.

It took me a few years reading, interviewing, and grappling with the relevant material to come to the following three very simple and basic understandings. First, we live in a world of objects. I am not now speaking of objects in a Freudian sense of the target of desire, but of the material, corporeal, external world separate from the psychic, interior world. In this sense, everything is an object: the lectern is an object, the door is an object, your chair is an object, even you are an object, and all the parts that make up “you.” The external world is a world of objects, the cosmos itself is an object, and these external objects are real. For the purposes of this article, we will call the real world of external objects, “A.”

Second, any time we have an objectively real experience with an external object, whether consciously or subconsciously, a complex process occurs that takes into account environment, psychological context, physical interaction, emotional status, motivation, desire, etc. and not only of our self-perception in the moment of experience, but also the perception of the external object related to, if it is sentient.3 From this process the mind forms a mental schema, or model of that object and the self’s relationship to it. This is called an internal object, or object representation. Our entire mental perception of ourselves and the world we live in exists in representations.4 This does not mean the external world is made up, like some subjective reality we create in our minds that doesn’t actually exist. It does mean the way we construct our interior world is. This representation forming is a dialectic process of internalizing external objects into a “mental map” we then use to interact with the external world. As Ana-María Rizzuto wrote: “There is no representation without object and no object without representation . . . we create the objects we find.”5 For the purposes of this series of articles, we will call these created internal object representations, “B.”

Third, the only way we are ever able to interact with the external world of objects is through the internal object representations we construct as part of our mental schema, and this unique relationship between the self and internal and external objects is called object relations, or what we will call “C.” As we encounter the external objects of the real world, the experience of those encounters (either positive or negative or neutral) shape our representations which then affects the nature of our relationship with those objects. If the chair you’re sitting in (A) collapses in a room full of people, that experience will shift your internal representation (B) of the external object, which will shift the way you relate (C) to all chairs, and perhaps significantly affect your relationship with chairs depending on the severity of your embodied experience.

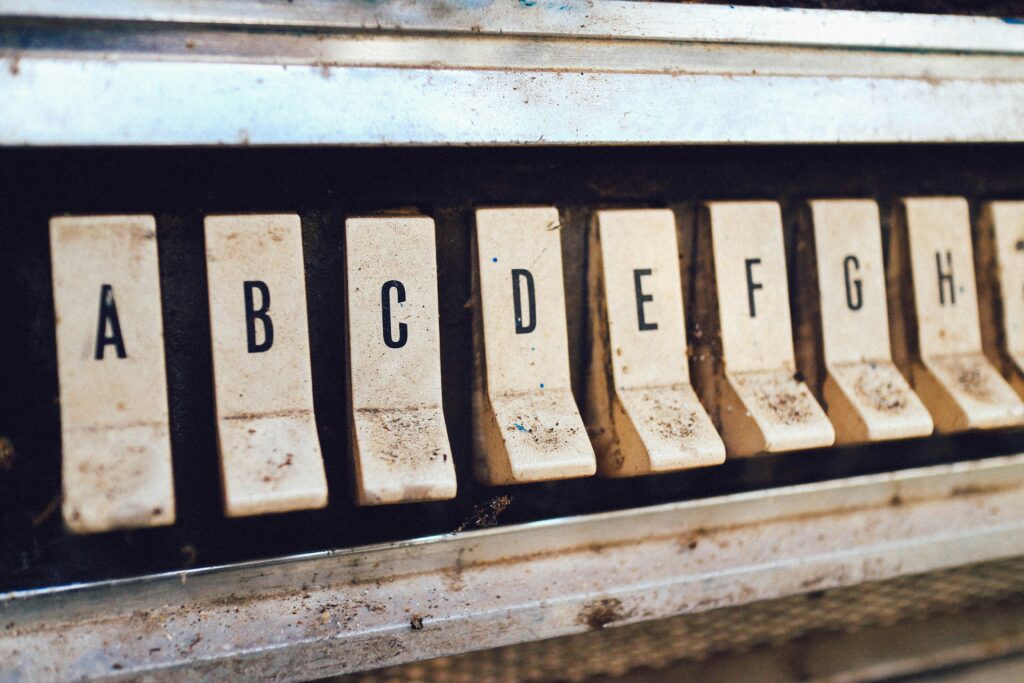

Before moving on to the next article, a critical point must be made that may seem overly obvious in concept but certainly is not in practice: our internal object representations are not the real, external objects themselves. In other words, B is not A. Never has been; never will be. That point cannot be stressed enough, and will be given attention in a later article. But, for now, a cursory look at the world of objects, object representations, and object relations (which took me years to process) ends up being as simple as A, B, C:

A. Objects

B. Object Representations

C. Object Relations